How to start contributing to open-source projects

One of the most common questions I'm asked by my computer science friends and lower-level students is how they can contribute to an open-source project. In order for me to organize and share my thoughts I thought I'd write something here.

First off, it's a good idea! Contributing to projects is a fantastic way to build experience, connections, and improve a piece of software you use or rely on. I've grown immensely through maintaining my few projects and contributing to a hand full of others. I've gained experience in community management, team communication, code review, dependency management, and the list goes on. This post is focused on programming, but don't forget that issue management, documentation, user support, and bug reporting are all valuable ways you can contribute.

That point about using open-source software is important. The first thing I tell my friends is they should first ensure they're using some before they attempt to contribute. There are few things that are more satisfying than fixing a bug that's been bugging you in a program written by someone else, and the motivation that provides is not inconsequential[^1]. As a maintainer, contributor, and extensive procrastinator I've seen and felt lack of motivation and burn-out from multiple perspectives, and know how daunting making a contribution can be. So to give you some ideas, here are some applications I use that you may want to try using (or may already use!), and a checklist for how to get started contributing to them:

- Firefox (really, it's (in some cases) as fast as Chrome now! Plus it helps you escape the Alphabet.)

- GIMP (GNU Image Manipulator Program, a free version of Photoshop.)

- VS Code (note that most of it is open-souce, but parts are not.)

- See VSCodium if you want a VS Code fork without Microsoft telemetry and licensing

And loads more. I didn't even mention the vast number of open-source software libraries and frameworks you likely already use. Maybe Next.js, Vue, or Flask are of interest to you, just to provide a few examples. And below is my framework for getting started.

The steps

- Find a project and feature or bug to work on: find one from experience or on their issue tracker/mailing list. Targeting a bug that bothers you or a feature you personally want is ideal due to the motivation aspect mentioned above. If the project is on GitHub these may be in the Milestone or Discussion pages. GitHub Explore filtered to languages you know or are interested in learning is a great place to start.

- Search for prior work or discussions: it's important your changes align with the maintainers vision, and you should double check that no one else is working on it. If they are or previously have, you can offer to team-up or ask for their advice.

- Familiarize yourself with the code base: depending on the size, it may not be feasible or sensible for you to grok the entire code base. Instead, try to learn just the parts you need. Feel free to ask the maintainers after searching the documentation and using the below tips if you need help:

- Read the README and CONTRIBUTING files, if they both exist[^2]

- Use a package explorer or the Unix

findutility to find directories and files of interest - Use

git grepto find identifiable or interesting messages/logs/strings in the code (an error alert's text, for example) - Use

git logto explore commits - Use

git blameto find out who to email or contact with questions- You can also check the README or look for a COMMUNITY file to find where to ask

- Get crackin': Work on the task, reaching out to the maintainers and/or community for help if necessary. Always be courteous, patient, and as clear as possible. Code samples and reproducible cases are king.

- Submit your work: Most likely, submitting your completed work will be done via a mailing list or over a code forge like GitHub and BitBucket. Refer to their documentation and the project's documentation to determine how to submit your changes.

- Wait, Fix, Repeat: It's likely you'll need to address some comments and make some changes to your initial work. That's okay! Address their comments and send it back to them. Few things feel worse than wasting a reviewers time (especially a volunteer like in many open-source projects), so be sure you self-review your code like you (hopefully) would an English paper.[^3]

A quick example:

...which you can read more about in my dedicated post.

- I wanted ambient light support on my Surface Pro 3 running Linux

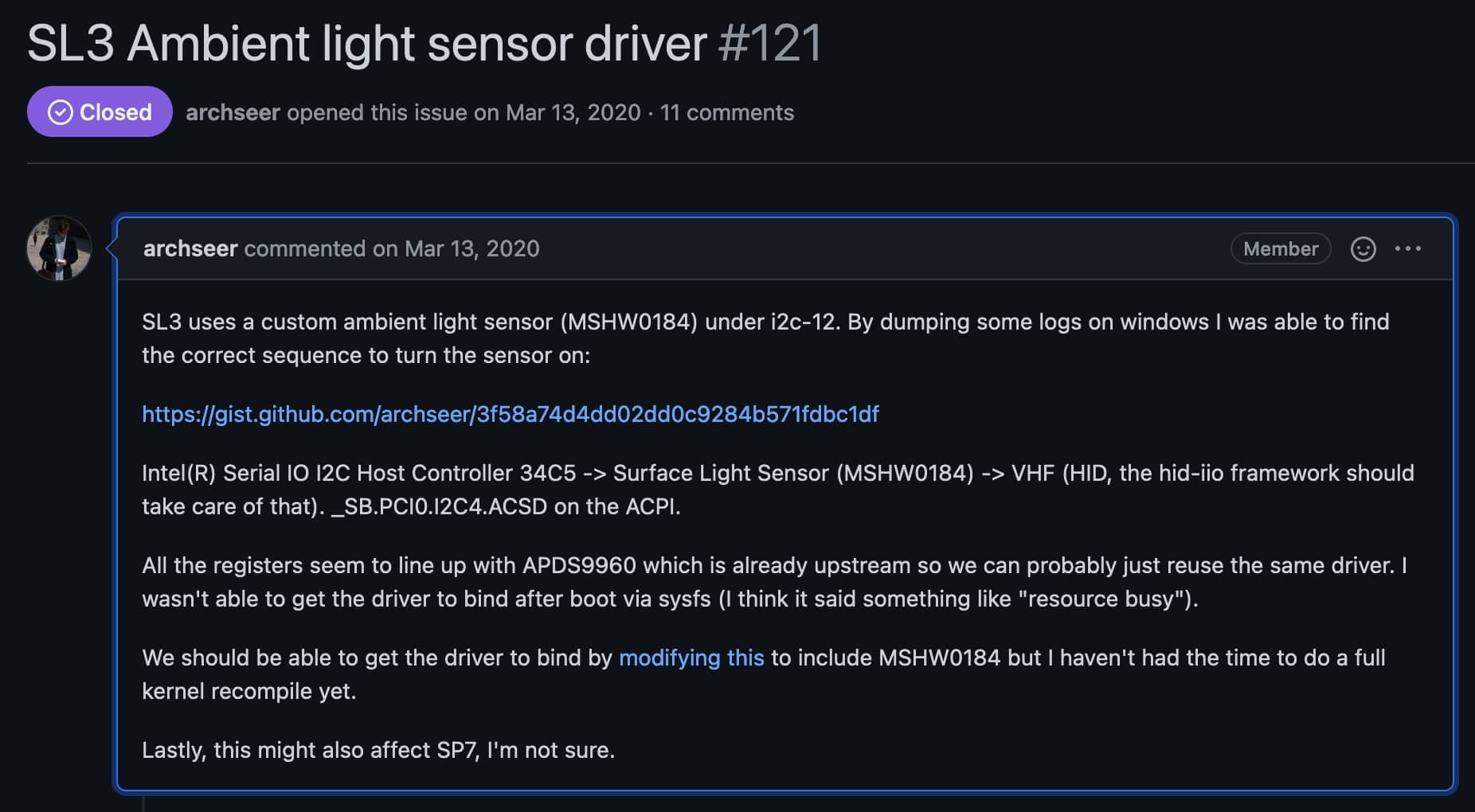

- I searched Google for information and luckily found this issue and repo:

- I searched the LKML for previous examples of minor driver adjustments and joined the #linux-surface IRC channel to talk with the other contributors to hear their ideas.

- After a few hours and with some help from IRC I determined how to have the device registered using the existing driver and pushed my code to GitHub.

- Once the code was reviewed by a few members of linux-surface I submit my patch set to LKML.

- It was released in Linux 5.11 🎉

In short

- Read the documentation

- Find an interesting problem to tackle that motivates you

- Discover and grow comfortable with your tools for grepping and exploring unfamiliar code bases

- Don't be afraid to reach out to the maintainers and community; develop communication skills

[^1]:. One of the few better feelings is fixing a bug in software you made that someone else reported. ⏎ [^2]:. If the README does not exist, consider that a red flag. If the CONTRIBUTING file does not exist, consider asking the maintainers if you could help draft one. ⏎ [^3]:. If you haven't worked professionally in CS yet, this is likely your first code review, and they're highly prevalent in the industry, so try extra hard to learn from your mistakes and take note of what you like and dislike about the review left for you. ⏎